Depleted Uranium |

|

Depleted uranium is a very dense metal; it is a by-product of the process by which natural uranium is enriched with the addition of radioactive isotopes taken from other uranium. The leftover uranium, drained of 40% of its original radioactivity, is called "depleted uranium." One of the most atrocious war crimes since WW2 is the use of depleted uranium (DU) munitions in Iraq and Afghanistan and Yugoslavia. Use of depleted uranium by the US military has been going on at least since the first Gulf War. Uranium metal is combustible and readily ignites when finely divided in air, a property known as pyrophoricity. Hence, when used militarily, or when present in an air crash or a fierce fire, the uranium may form large quantities of dust containing a mixture of uranium oxides that can be ingested or inhaled. A series of research reports and articles have been published which claim that the use of DU munitions has had serious negative effects on the health of soldiers, local populations, and the environment.

Depleted uranium is a very dense metal; it is a by-product of the process by which natural uranium is enriched with the addition of radioactive isotopes taken from other uranium. The leftover uranium, drained of 40% of its original radioactivity, is called "depleted uranium." One of the most atrocious war crimes since WW2 is the use of depleted uranium (DU) munitions in Iraq and Afghanistan and Yugoslavia. Use of depleted uranium by the US military has been going on at least since the first Gulf War. Uranium metal is combustible and readily ignites when finely divided in air, a property known as pyrophoricity. Hence, when used militarily, or when present in an air crash or a fierce fire, the uranium may form large quantities of dust containing a mixture of uranium oxides that can be ingested or inhaled. A series of research reports and articles have been published which claim that the use of DU munitions has had serious negative effects on the health of soldiers, local populations, and the environment.

During the Iraq War U.S.A has used over 2200 tons of radioactive DU weapons. Since then, there have been mysterious illnesses and post-war birth defects reported among Gulf War veterans and civilians in southern Iraq, as well as radiation related illnesses in UN Peacekeepers serving in Yugoslavia. The greatest effects of DU have been on the local populations that live in contaminated areas.

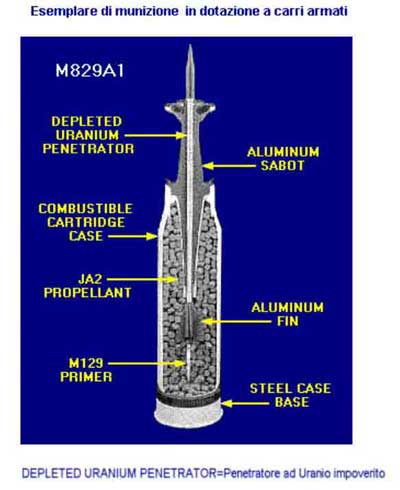

In the manufacture of nuclear material, natural uranium ore is extracted and processed to form enriched uranium for nuclear power or nuclear weapons. Depleted uranium (DU) is the by-product of this uranium enrichment process. Made from this low-level radioactive waste, DU in the metallic form has high density and hardness as well as pyrophoric properties, which makes it superior to classical tungsten as a protective covering on shooting munitions. Due to its high density, it has been used in the manufacture of defensive military armour, armour piercing shells, conventional munitions, and some missiles mainly by the United States, but also by other countries such as Britain. DU is very low cost and readily available, it is quite profitable to use, a bottom-line business model that, when combined with military production needs, is a defining feature of the Military-Industrial complex; and when this logic results in the use of such ethically questionable materials, that’s an example of organizational deviance.

In the manufacture of nuclear material, natural uranium ore is extracted and processed to form enriched uranium for nuclear power or nuclear weapons. Depleted uranium (DU) is the by-product of this uranium enrichment process. Made from this low-level radioactive waste, DU in the metallic form has high density and hardness as well as pyrophoric properties, which makes it superior to classical tungsten as a protective covering on shooting munitions. Due to its high density, it has been used in the manufacture of defensive military armour, armour piercing shells, conventional munitions, and some missiles mainly by the United States, but also by other countries such as Britain. DU is very low cost and readily available, it is quite profitable to use, a bottom-line business model that, when combined with military production needs, is a defining feature of the Military-Industrial complex; and when this logic results in the use of such ethically questionable materials, that’s an example of organizational deviance.

In any war, soldiers and civilians are told that the fight is for their country and the safety of her borders, the preservation of their rights and way of life, their pride, and the advancement of their society. Nonetheless, history has shown over and over that wars have always been destructive and merely power plays for the profit of elite minorities, and have never been designed for the well being of the people or the advancement of society. From the Roman, Greek and Persian empires through to today’s conflicts, the purpose of war has been all about more wealth and more power for the men in control, and the consequences have been more and more destruction and civilian death as technological advances make mass killing easier. One of the more modern “advances” in military innovation is depleted uranium (DU), which is a low-level radioactive by-product waste of uranium enrichment process.

T he chemical toxicity of DU has been established by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (1999), and the World Health Organization (WHO, 2001) in their recent report also showed that, quite likely, the major hazard from DU is chemical rather than radiological. The kidney is the organ primarily affected by ingested uranium and dysfunction caused by uranium chemical toxicity has been proven in both animal and human populations. In terms of Gulf War syndrome, which is described as a spectrum of symptoms and medical disorders, not only those related to the kidney, there are likely to be a combination of causative factors; not just the single factor of DU exposure.

he chemical toxicity of DU has been established by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (1999), and the World Health Organization (WHO, 2001) in their recent report also showed that, quite likely, the major hazard from DU is chemical rather than radiological. The kidney is the organ primarily affected by ingested uranium and dysfunction caused by uranium chemical toxicity has been proven in both animal and human populations. In terms of Gulf War syndrome, which is described as a spectrum of symptoms and medical disorders, not only those related to the kidney, there are likely to be a combination of causative factors; not just the single factor of DU exposure.

The Gulf War may have been short in duration, but its consequences endured for years after the fighting came to an end (Gulf War and Health, 2006). Many returning Gulf War veterans began reporting numerous health problems that they believed to be associated with their service in the Persian Gulf. Healthy and fit soldiers were reporting that they could no longer engage in normal daily activities, much less the robust tasks they participated in with the military. Their symptoms were common and included fatigue, memory loss, severe headaches, muscle and joint pain, and rashes (Fukuda et al., 1998). Fukuda described the symptoms as fatigue, mood and cognition problems such as feeling depressed, having difficulty remembering or concentrating, feeling moody, feeling anxious, having trouble finding words, and having difficulty sleeping. There were also associated musculoskeletal problems like joint pain, joint stiffness, and muscle pain (Fukuda et al., 1998). The veterans wanted to know what had happened, why they were so ill, what could be done to make them better, and whether the military was responsible for their predicament and would do something to help them. As affected veterans began finding each other and seeing the extent of the problem, they took their case to the media, to Congress, to the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and to the Department of Defense (DoD). Many Gulf War veterans claim that toxic exposure during their service in Iraq and Kuwait caused a variety of illnesses and disorders. Something like 70,000 of them have required treatment for service-related ailments (Haley et al. 1998). Yet, the National Academy of Science (1994) concluded:

“No studies report human deaths or other health effects from oral exposures to uranium oxides. Mortality, usually from renal failure, can be induced in animals at very high oral intake levels. No human studies were found in the peer reviewed published literature that showed respiratory, cardiovascular, hematological, musculoskeletal, hepatic, endocrine, dermal, ocular, body weight, or other system effects in humans exposed to uranium compounds.”

As activists and oppositional scientists became more aware of the problems of veterans and war-zone populations in their contaminated living areas, a popular epidemiology developed to examine this toxic tool being used so callously by power elites. Brown and Mikkelsen (1990, 125) showed the importance of epidemiological research into the distributions of a disease or a physiological condition and the factors that influence these distributions. In the case of DU, veterans and activist raised the issue and the need for the epidemiologic studies essential in assessing the relationship between exposure to depleted uranium (DU) and health outcomes of the veterans and the people living in conflict zones. The elements of these studies included identification of a relevant study population of adequate size, and appropriate assessment and accurate measurement of uranium exposure in the population. The examination of the extensive health problems of returning veterans and war-zone populations in Iraq and the Balkans, as well as an increase in the public’s knowledge of DU and its consequences, resulted in countless articles in popular and scientific journals, followed by mass media reports such as Global Research’s report about DU & public health:

“The public health effects of the use of Depleted Uranium (DU) weapons are such that their use can be considered per se violations of the war crime of Genocide under the Statute of the International Criminal Court. The documented devastating effects of DU weapons on public health include; the negative impacts of radiation from nuclear weapons and nuclear weapons testing, nuclear power and nuclear reactors, and depleted uranium weaponry, which include but are not limited to the following: Cancer; Birth defects; Chronic diseases caused by neurological and neuromuscular radiation damage; Mitochondrial diseases (Chronic fatigue syndrome, Lou Gehrig's, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer's; Heart and brain disorders; Global DNA damage in men's sperm; Infertility in women; Learning disabilities; Mental illness; Diabetes; Infant mortality and low birth weight increases, Atmospheric testing impacts on the environment (Global Research, 2007).”

Concerns and debates over reports about the effects of DU led to the launch of investigations into veteran health concerns. Various aspects of the problem were studied by a Presidential Advisory Committee (PAC), the General Accounting Office (GAO), a special investigation unit of the Committee on Veterans Affairs of the U.S. Senate, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Institute of Medicine (IOM), and independent researchers. Depleted uranium was used for the first time in Gulf War. With veterans claiming that their problems and symptoms are related to Gulf War, these studies have compared Gulf War veterans to other contemporary military veterans to determine such things as whether they have higher hospitalization rates or a greater incidence of reproductive problems or higher mortality rates. The result has been studies such as that of Hernandez et al, which reported:

However, these professional responses are not universal, and organized community groups have been able to collaborate with their own experts and oppositional scientists to help define exposures, organize health studies, and bring the results to public and official attention, thus highlighting the organizational deviance of a government and a military that would expose their own people (veterans) as well as populations in conflict zones to the waste by-product of the processing of radioactive uranium. Activist and oppositional scientist have encountered firm resistance to community involvement in health studies related to DU, with some professionals perceiving a need to defend their professionalism.

One interesting community action group keeping the DU issue alive consists of the women involved in the Gulf War Illness movement as a forum for airing accumulated grievances about health concerns, financial hardships, and emotional problems (Shriver, Miller, & Cable, 2003). This informal grouping formed in response to the health problems that many veterans of the 1991 Gulf War attributed to exposures they had to various pollutants, weapons, vaccinations, and medications during their military service. According to the U.S. Persian Gulf War Registry, the government’s official database for veterans’ complaints, about 200,000 Gulf War veterans have reported a variety of debilitating health problems, including memory loss, headaches, skin rashes, mood swings, aching joints, blurred vision, abdominal pain, diarrhea, chemical sensitivities, chronic fatigue, and birth defects in babies borne by female veterans and by male veterans’ wives. In its usual display of organizational deviance, the government initially made no attempt to explore their concerns and rejected veterans’ claims on the grounds of insufficient data to demonstrate a scientific correlation between their illnesses and the risks posed in the Gulf War. Male and female veterans and spouses of veterans of the 1991 Gulf War responded by forming about fifty grassroots organizations nationwide to demand government recognition of Gulf War Illness (NGWRC 1997). Shriver et al (2003) refer collectively to this network of grassroots organizations as the Gulf War Illness movement.

Women affected by the issue, either as veterans or as the wives of veterans, used the Internet as a tool in a form of popular epidemiology to research medical information, and then provide their findings, plus emotional support, to geographically dispersed veterans. This type of activism transformed these women by awarding them with a sense of empowerment and a somewhat broadened concern for social justice. Shriver et al used in-depth interviews, participant observation, and document analysis to examine this group of women whom they included in the Gulf War Illness movement. They interviewed women experiencing illness and difficulties either themselves or through their husbands and documented their health concerns, financial hardships, and emotional problems. They also reviewed government documents by agencies such as the Presidential Advisory Committee and the General Accounting Office, social movement organization newsletters, and newspaper articles to enhance their understanding of the controversy and highlight the military’s organizational deviance in abandoning their veterans.

The Gulf War Illness movement women have taken leadership positions and been active in protest activities, forming support groups, and searching for information about the illnesses. They had three main grievances that made them eager to participate in the Gulf War Illness movement: denial of access to government health care, financial hardship, and emotional problems (Shriver et al, 2003). Denial of health care coverage was a result of the government’s rejection of veterans’ claims that their illnesses and their children’s birth defects were attributable to military service in the Gulf War. Many women reported that they were fighting as much for medical coverage for their children as for themselves or their husbands. One veteran who bore a child with a serious birth defect shortly after she returned from the Persian Gulf offered her perception of the government’s intransigence:

“They are looking at a cost problem. They don’t want to admit it because they are afraid we are going to sue. But there are all kinds of ‘outs’ they could take and still help the people that really need it.”

Women activists reported both positive and negative effects of their involvement in the Gulf War Illness movement. The positive effects they described involved gaining a new sense of empowerment by participating in a form of popular epidemiology and by gaining new insights and experiences in working for social justice. The negative effects were increased marital tensions and withdrawal from their previous social networks of friends and neighbors.

Many studies on depleted uranium have examined the danger of this new form of ordinance, and the questions raised should have resulted in at least a temporary moratorium on the use of DU but the stubborn organization deviance of government agencies means that this toxic material is still being used. As an overview of the various investigations into this issue, I have below outlined a few reports:

Bukowski & Lopez (1993) carried out one of the earliest researches into DU. They discussed an instance of groundwork popular epidemiology that was carried out by community activists in Socorro County, New Mexico where a populated rural area found itself downwind of a DU-weapons testing site. Involved at the site was the Institute of Mining and Technology's Terminal Effects Research and Analysis (TERA) division, and in a letter addressed to TERA, a community activist described birth defects among infants born in Socorro County between 1979 and 1986. The writer said she was referencing cases reported in the State of New Mexico's passive birth defects registry. The writer also reported two infants with birth defects in 1985 that were known to her but not recorded in the registry. In a county with about 250 births per year, the writer reported 5 infants born with hydrocephalus, one of which was not recorded in the registry. There was nothing remarkable about 16 other abnormalities she enumerated. All the cases of hydrocephalus occurred between 1984 and 1986. In 1998 another community activist requested and received a count of all hydrocephalic births in New Mexico and in Socorro County for the years 1984 – 1988 from the State Department of Health. The registry report documented a total of 19 infants born with hydrocephalus in New Mexico during those 5 years; 3 of them Socorro County residents (Bukowski, & Lopez 1993).

Gunther (2000), the president of the Austrian-based humanitarian and relief organization Yellow Cross International spent much time in Iraq and has had an appointment as Professor of Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology at the University of Baghdad. Shortly after the 1991 Gulf War, he began to publicize his observations of catastrophic and ongoing ill health and distinctive patterns of abnormality among the Iraqi population.

In Iraq, the misuse of radioactive materials has had substantial effects on the environment and on the people and animals that depend on it when toxic substances leak into the ground, dissolve through the air, and taint water and food supplies, (Browne, 2003). Iraq’s national nuclear inspector has forecasted that over a thousand people could die of leukemia as a result. Barrels used to store depleted uranium were sold to villages, dumped and rinsed of their contents and used for storing basic amenities like water, cooking oil and tomatoes, or they were used to transport milk to distant regions, thus making this critical problem increasingly widespread.

Brown (1990) has suggestions on how to make sure our living habitat is safe for us and for our future generations. He suggests we step up public pressure on responsible parties and find out who has the greatest influence on decision making so that political action can be most effective. Environmental activism has expanded our frontiers of knowledge, which in turn can increase environmental protection. We must re-conceptualize the causal linkage between substance and disease and rethink the disease process itself. He also emphasizes public participation and involvement and awareness about popular epidemiology even though, as in many areas of social action, it contains elements of ambivalence. We as a society must focus on corporate and governmental responsibility to stop crime and cover-up (Brown, 1990).

Having said all of the above, it still seems that the people who are most aware of the effects of any particular war are the ones who are involved in it such as soldiers, reporters, some intellectual readers, the military establishment, and most tragically, the people who live in the conflict zones. The majority of the world’s population, especially in the western world, are focused on their daily lives of bills and vacations and entertainment. They don’t know anything about how an Iraqi farmer and his family deal with a DU-exposed member. Ordinary people won’t know about leukemia and other cancers among servicemen who took part in the 1991 Gulf War or in the more recent operations in the Balkans, and their ongoing battles with the system to receive compensation or to prevent the same thing from happening to others now or in the future. Yet Brown (1990) suggests that the corporate responsibility for toxic waste contamination is integrally linked to the ordinary workings of the economic system; meaning that government involvement will not necessarily erase that link. Also, since both corporations and government have proven inimical to environmental protection, especially given their close links within the Military-Industrial complex, person harmed by pollution must of necessity turn to the courts, which means litigation will continue to be an important avenue for victims of toxic exposure (Brown, 1990).

References:

Al-Taha, S. (1994). A survey of a genetic clinic patients for chromosomal, genetic syndromes and congenital malformations as detected by clinical and chromosomal studies The International Scientific Symposium on Post War Environmental Problems in Iraq. 105-106.

Bem, H. Bou-Rabee, F. (2004). Environmental and health consequences of depleted uranium use

in the 1991 Gulf War. Environment International, pp. 123– 134

Brown, P., Mikkelsen, E. J., (1990). No Safe Place: Taking Control, Popular Epidemiology.

Brown, P., Mikkelsen, E. J., (1990). No Safe Place: Making it safe, Securing Future Health, P. 165, 184.

Browne, A. (2003) Iraqi Chernobyl uranium fears The Times. The Australian. http://www.theaustralian.news.com.au/printpage/0,5942,6515830,00.html

Bukowski G, Lopez D, (1993). Uranium Battlefields Home and Abroad: Depleted Uranium Use by the Department of Defense. Citizen Alert & Rural Alliance for Military Accountability, Carson City Nevada: Reno; P. 166.

Fetter, S., & Hippel, F. N., (1999). The Hazard Posed by Depleted Uranium Munitions. Science & Global Security, Volume 8:2, pp.125-161

Fukuda, K., Nisenbaum, R., Stewart, G., Thompson, W. W., Robin, L., Washko, R. M., et al. (1998). Chronic multisymptom illness affecting Air Force veterans of the Gulf War. JAMA, 280, 981–988.

Global Research, April 3, 2007

Gunther, S. H. (2000). Severely Maimed Soldiers, Deformed Babies, Dying Children. Freibburg, Germany.

Gulf War and Health (2006): National Academy of Sciences. A Review of the Medical Literature Relative to the Gulf War Veterans’ Health Volume 4. Health Effects of Serving in the Gulf War http://books.nap.edu/catalog/11729.html

Hernandez, L. M.; Durch, J. S.; Blazer, D. G. (1999). Gulf War Veterans: Measuring Health. Washington, DC, USA: National Academies Press. P. 11-13. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/athabasca/Doc?id=10040982&ppg=11

Notional Gulf War Resource Center (1997).

Shriver, T. E., Miller, A. C, & Cable, S. (2003). Women's Involvement in the Gulf War Illness Movement. The Sociological Quarterly.